Tuesday, January 15, 2019

Trains on Stevens Pass in July 2000

I took these pictures in July of 2000 when my family visited Stevens Pass in the Cascade Mountains of Washington. This first train was an eastbound freight train that was passing slowly through the town of Skykomish. It was led by Burlington Northern #7130, a 3,000-horsepower SD40-2 that was built by the Electro-Motive Division of General Motors in January 1979.

The second unit in the train, Burlington Northern Santa Fe #3014 was originally built as a 3,000-horsepower GP40 by the Electro-Motive Division of General Motors in December 1966 as Chicago, Burlington & Quincy #182. After the CB&Q was merged into the Burlington Northern on March 2, 1970, it became Burlington Northern #3012. On November 13, 1989, it was rebuilt by Morrison-Knudsen in Boise, Idaho, as a GP40M, and became Burlington Northern #3515. After the Burlington Northern and the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe merged to form the Burlington Northern Santa Fe on September 22, 1995, it became BNSF #3014 on September 25, 1998, but was still wearing BN colors.

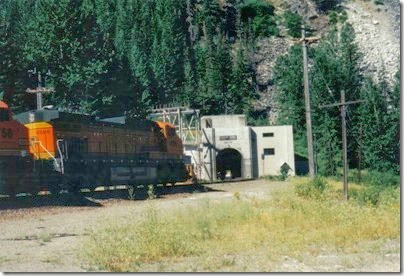

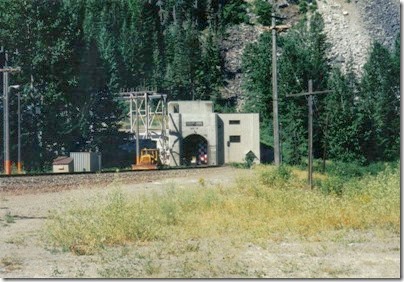

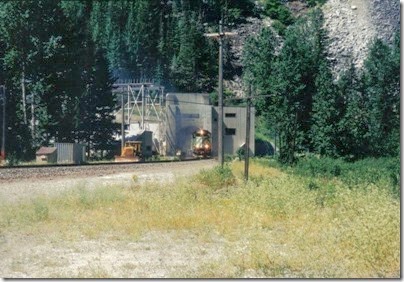

We went to the east portal of the 7.79-mile Cascade Tunnel at Berne, Washington. This tunnel opened on January 12, 1929, and was originally electrified for the use of electric locomotives. A ventilation system was completed at this end of the tunnel on July 31, 1956, to allow diesel locomotives to be used in the tunnel. The door at this end of the tunnel forces the fumes to be blown out the other end; when the ventilation system is running, the door stays closed until an approaching train is with 3,200 feet of the portal.

This is the highest point on the Stevens Pass line, so this westbound freight train had been working hard to climb to this point, and would now be able to enter the tunnel and start down the other side.

Leading this train was Burlington Northern Santa Fe #4699, a 4,400-horsepower Dash 9-44CW that was built by General Electric in April 2000.

This freight train also featured a pair of mid-train helper locomotives. Burlington Northern Santa Fe #4629 is a 4,400-horsepower Dash 9-44CW that was built by General Electric in January 2000.

The original door at the east portal of the Cascade Tunnel opened vertically, but in 1997, the ventilation system was rebuilt, and a new door was installed that slides to the side.

This is the same eastbound train that we had seen earlier at Skykomish. The ventilation fans are still running with the door open, so some of the exhaust can be seen escaping from this end of the tunnel.

Having completed its climb this train can now continue down the east side of Stevens Pass.

Wednesday, March 19, 2014

Tumwater Dam

Located 25 highway miles east of Berne, in the Tumwater Canyon, this dam was built by the Great Northern Railway to produce the electricity for the electric locomotives that pulled trains through both Cascade Tunnels.

The Great Northern mainline went down Tumwater Canyon and past this plant until 1928, when the new Chumstick Line was opened that bypassed the canyon and was shorter and straighter with less grades.

The city of Leavenworth was also bypassed, leaving the town virtually isolated until U. S. Highway 2 was built through Tumwater Canyon, directly on the roadbed of the Great Northern's original route, where it remains today.

A sign at the dam explains its historical significance.

HISTORIC TUMWATER DAM

The Tumwater Hydroelectric Project was constructed from 1907 to 1909. At that time, the hydroelectric project was the largest west of Niagara Falls. The project was constructed by the Great Northern Railway Company to produce power for electric locomotives traveling through the old Cascade Tunnel on the Stevens Pass route.

Electrification of the three miles of the line brought an end to the serious smoke and gas conditions in the tunnel resulting from the coal burning locomotives. Four 100-ton electric locomotives were in service on the trolley line to pull passenger and freight trains through the tunnel, which was abandoned in 1929 upon construction of a new eight-mile-long Cascade Tunnel. The locomotives were the first in the United States to utilize the principle of regenerative braking, returning power to the lines on the downhill grade.

From the Tumwater Dam, water was delivered through a penstock to a powerhouse over two miles downstream. A bridge was constructed across the river to allow railroad access to the dam construction site. The bridge was then utilized to carry the penstock to the powerhouse. The bridge still stands, and serves as a link to the old penstock route. The powerhouse was a concrete and brick structure that housed three waterwheels and three 2,000 kilowatt generators.

The Tumwater Hydroelectric Project was closed in 1956. By that time, the railroad had converted to diesel engines. The project was purchased by the Chelan County public Utility District in 1957. The powerhouse and related generating facilities were subsequently removed.

The Tumwater Dam is now equipped with modern fish passage facilities to assist adult salmon and steelhead returning to their spawning grounds.

HISTORIC PROJECT STATISTICS

DAM

Groundbreaking............July 6, 1907

Length...........................400 Feet

Height...........................23 Feet

Construction Cost.......$100,000

Fishway........................Newly Constructed 1987

HEAD..............................200 Feet

PENSTOCK

Material.......................Wood & Steel

Length.........................11,654 Feet

Diameter.....................8.5 Feet

SURGE TANK

Height.........................210 Feet

Capacity......................1 Million Gallons

POWER HOUSE

Generators..................Three, 2,000 kilowatts each 25 Cycle, A.C.

Turbines......................Three, Francis type 4,000 horsepower each

Historical Photo:

Great Northern Tumwater Powerhouse, circa 1908 (UW)

East of Leavenworth, Highway 2 meets up with the railroad again, which returns to its original alignment through Wenatchee to Spokane and beyond. From this point on, there isn't much of historical interest to non-rail enthusiasts along the route for quite a distance beyond Stevens Pass, so that concludes this expedition.

Berne, Washington

East Portal of the Cascade Tunnel in 1998.

Berne is the site of the east end of the current Cascade Tunnel. It is fairly easy to find, as Highway 2 passes almost directly over the tunnel entrance, and the current portal is visible from the highway.

The new Cascade Tunnel opened for service on January 12, 1929. When the tunnel first opened, the east portal looked identical to the west portal at Scenic, and electric locomotives were used in the tunnel.

Historical Photos:

East Portal during construction, 1927 (UW)

Workers in Mill Creek Bunkhouse at Berne, 1928 (WSHS)

Electric Locomotive #5011, 1928 (UW)

Officials prepare to open tunnel, January 12, 1929 (UW)

Officials opening the new tunnel, January 12, 1929 (UW)

Officials throw a switch for the first Oriental Limited through the tunnel, January 12, 1929 (UW)

First Oriental Limited through tunnel, Jan. 12, 1929 (UW)

Officials in front of new tunnel, January 12, 1929 (UW)

Empire Builder, circa 1929 (UW)

By late 1947, the Great Northern was using diesel locomotives on its passenger trains through the Cascade Tunnel, including the Empire Builder, Oriental Limited, and Fast Mail, eliminating the change of motive power at Wenatchee and Skykomish. Test trips had shown that diesel locomotives could pull fast-moving passenger trains through the tunnel, but with heavy freight trains, the heat generated by the exhaust gases raised the air temperature inside the tunnel enough to cause engine shutdowns. This is because the train acts as a piston in the tunnel, pushing the cooler air in front of it and leaving the locomotives surrounded by the hot air from their own exhaust. By 1952, the Cascade Division was effectively completely dieselized, with the last steam run taking place from March 23-30, 1953 when a stored 4-8-2 pulled a weed burner train from Seattle.

In the early 1950s, the Great Northern tested a pair of new General Electric experimental E2b electric locomotives. Built in 1951, these 2,500-horsepower units were copies of four units sold to the Pennsylvania Railroad. They had B-B trucks, painted black, and assigned numbers 5020 and 5021. The Great Northern decided they lacked adequate pulling power at the low speeds that were typical on the 2.2% grades. They were returned to GE and sold to the Pennsylvania in March 1953.

The Great Northern had studied extending the electrification east to Spokane in 1930, and west to Seattle in the early 1950s. Both times they found no economic justification for an extension. In 1955, further studies concluded that the electrics cost half as much to operate as steam power, but twice as much as diesels. The Great Northern determined that diesel locomotives could pull freight trains through the Cascade Tunnel if the tunnel was equipped with a ventilation system, and in 1956 the Morrison-Knudsen Company of Boise, Idaho, was hired to install such a system at a cost of $650,000.

East Portal of the Cascade Tunnel in 1994. Photo by Cliff West.

At the east end of the tunnel, a new portal with a vertical lift steel door and a pair of 6-foot fans driven by 800-horsepower electric motors turning at 1,150 rpm were installed. With the door closed, this system supplied a fresh air flow of 220,000 cfm. When a train was in the tunnel, only one fan was used; the second fan came on once the train exited the tunnel. With eastbound trains, the door closed when the train entered the west portal with one fan running and opened when the train came within 3,200 feet of the east portal, then closed again when the train cleared and both fans ran for 28 minutes to clear the exhaust from the tunnel.

The ventilation system was placed in service on July 31, 1956, and diesel locomotives took over all operations over Stevens Pass. The Z-1 class electrics were sold for scrap and the Y-1 and Y-1a electrics were sold to the Pennsylvania Railroad; the Y-1s became PRR Nos. 1-7 and the Y-1A was used for parts. W-1 No. 5018 was sold to the Union Pacific Railroad for conversion to a coal turbine locomotive, and No. 5019 was scrapped.

Historical Photos:

Diesel at East Portal, Apr 1958 (gngoat.org)

Diesel at East Portal, July 27, 1973 (rrpicturearchives.net)

The Great Northern was merged into the Burlington Northern Railroad on March 2, 1970. Between July 1989 and May 1990 the Burlington Northern undertook a $4.8 million project to cut parallel notches in the tunnel lining to provide clearance for new double-stack container trains.

East Portal of the Cascade Tunnel in 2000.

In 1997, the tunnel's ventilation system was rebuilt, with this result. Where the original door opened vertically, like a garage door, the new door opens to the side. In any event, operations have remained essentially the same over the years. If a train enters the tunnel from the west, the door closes and the fans turn on, forcing the exhaust out behind the train. The door remains closed until the train is a quarter-mile from the east end, when the door opens automatically to let the train out. If a train enters from the east, the fans come on immediately and the door closes once the train is fully inside. The exhaust is forced out ahead of the train, and the door at the east end reopens when the train has cleared the tunnel. In either case, the fans continue to run for 30 minutes after a train has left the tunnel to fully clear the tunnel of diesel exhaust fumes.

Here are some pictures of the East Portal of the Cascade Tunnel and trains at Berne.

East Portal of the Cascade Tunnel in 1994.

East Portal of the Cascade Tunnel in 1994.

Door opening on the East Portal of the Cascade Tunnel in 1994.

Burlington Northern GP40M #3518 emerging from the East Portal of the Cascade Tunnel with an eastbound freight train in 1994. Photo by Cliff West.

Burlington Northern GP40M #3518 emerging from the East Portal of the Cascade Tunnel with an eastbound freight train in 1994.

Burlington Northern GP40M #3518 emerging from the East Portal of the Cascade Tunnel with an eastbound freight train in 1994. Photo by Cliff West.

BN GP40M #3518 with an eastbound freight train at Berne in 1994.

BNSF C44-9W #4699 at Berne with a westbound freight train in 2000.

BNSF C44-9W #4699 heading into the East Portal of the Cascade Tunnel with a westbound freight train in 2000.

BNSF C44-9W #4629 as a helper in a westbound freight train at Berne in 2000.

Door closing on the East Portal of the Cascade Tunnel in 2000.

Burlington Northern SD40-2 #7130 emerging from the East Portal of the Cascade Tunnel with an eastbound freight train in 2000.

Burlington Northern SD40-2 #7130 emerging from the East Portal of the Cascade Tunnel with an eastbound freight train in 2000.

East Portal of the Cascade Tunnel in 2002. Photo by Cliff West.

East Portal of the Cascade Tunnel in 2002. Photo by Cliff West.

Door opening on the East Portal of the Cascade Tunnel in 2002.

Photo by Cliff West.

Door opening on the East Portal of the Cascade Tunnel in 2002.

Photo by Cliff West.

Door opening on the East Portal of the Cascade Tunnel in 2002.

Photo by Cliff West.

Eastbound Train inside the Cascade Tunnel in 2002. Photo by Cliff West.

BNSF SD75M #8229 emerging from the East Portal of the Cascade Tunnel with an eastbound intermodal train in 2002. Photo by Cliff West.

BNFS SD75M #8229 emerging from the East Portal of the Cascade Tunnel with an eastbound intermodal train in 2002. Photo by Cliff West.

BNSF C44-9W #756 in an eastbound intermodal train at Berne in 2002.

Photo by Cliff West.

Norfolk Southern C40-9W #9585 in an eastbound intermodal train at Berne in 2002. Photo by Cliff West.

BNSF C44-9W #4917 emerging from the East Portal of the Cascade Tunnel with an eastbound intermodal train in 2002. Photo by Cliff West.

Continue to Tumwater Dam…

Bygone Byways Interpretive Trail

Along the Bygone Byways Interpretive Trail in 2000.

Most of the Great Northern’s original roadbed between Cascade Station and Berne has been turned into roads, either as part of the Cascade Scenic Highway (now U.S. Highway 2), which opened in 1935, or as U.S. Forest Service roads. However, a short section of the roadbed survives as a hiking trail called the Bygone Byways Interpretive Trail.

Rock Cut along the Bygone Byways Interpretive Trail in 2000.

This short trail passes through a rock cut used by the railroad, as well as a few historical artifacts and a view of Nason Creek.

My sister Andrea in the cut on the Bygone Byways Interpretive Trail in 2000.

Continue to Berne, Washington…

Cascade Station

East Portal of the old Cascade Tunnel in 1994.

The east portal of the old Cascade Tunnel, and the site of Cascade Station, originally called Tunnel City, can be reached by following Forest Service Road 6980. This road leads right up to the tunnel, and you can drive right up to the portal, though obstructions inside prevent actually driving through. Some searching will reveal foundations from buildings at Cascade Station as well. Cascade Tunnel Station was at an elevation of 3,382 feet above sea level, and was the highest point on the Stevens Pass line once the Cascade Tunnel opened.

East Portal of the old Cascade Tunnel in 1994.

This Cascade Tunnel was abandoned in 1929 with the rest of this route when the new Cascade Tunnel opened between Scenic and Berne. The land was turned over to the U. S. Forest Service, which blocked the portals of the tunnel for many years. Eventually, the U. S. Government reopened the tunnel and used it as a storehouse for a time, but was largely ignored until the Iron Goat Trail was built to the west portal.

East Portal of the old Cascade Tunnel in 2000.

Historical Photos:

Train exiting the East Portal (UW)

Last train over old line at Berne, January 12, 1929 (UW)

East Portal, with doors when used as storage (UW)

East Portal, with doors when used as storage (UW)

Continue to Bygone Byways Interpretive Trail…

Switchbacks and the First Cascade Tunnel

West Portal of the old Cascade Tunnel in 2000.

The tunnel between Scenic and Berne was not the first Cascade Tunnel. At the end of the Iron Goat Trail is the west portal of the first 2.63-mile Cascade Tunnel, built in 1900 between Wellington & Cascade Station. Before building this tunnel, the Great Northern used a series of switchbacks to get over the pass. The map below shows the switchbacks and the first Cascade Tunnel.

These switchbacks were part of the original route over Stevens Pass from 1893. The Great Northern always planned to tunnel between Cascade Station and Wellington, but James J. Hill was most concerned about completing the route to Seattle, so to speed the completion of the line, the 12-mile series of switchback was built as a temporary measure. The switchback route was slow and treacherous; trains has to reverse direction several times, ultimately running in reverse over the summit, as they climbed up steep 3% to 4% grades through sharp 12-degree curves to an altitude of over 4,000 feet, over 650 feet above Cascade Station, where the highest point would be with the tunnel in use. Trains were limited to 1000-feet in length, including three locomotives needed to pull trains over the switchbacks. There was never a serious accident over the switchbacks in the five years they were used, but they were a bottleneck; it took a train 75 minutes to travel the 12.5 miles of switchbacks.

Historical Photo:

View of switchbacks on west slope, 1907-08 (WSHS)

Before the switchbacks were built, the Great Northern's primary freight locomotives were 2-6-0 Moguls built by the Rogers Locomotive Works. With 20,085 pounds of tractive effort and 87,000 pounds of weight on their drivers, they could only handle 3 or 4 cars on the 4% grades of the switchbacks. In 1891, the Great Northern received 4-8-0 locomotives from the Brooks Locomotive Works for pusher and road service. They had 28,925 pounds of tractive effort with 132,000 pounds on the drivers, and introduced the Belpaire firebox to the Great Northern. In 1892 the Brooks Locomotive Works of Dunkirk, New York delivered 2-8-0 Consolidations for road service with 26,080 pounds of tractive effort, 120,000 pounds on the drivers, and 180 pounds of boiler pressure. Originally ordered for service in the Rocky Mountains, the 2-8-0s and 4-8-0s came to Stevens Pass in time to help complete the switchbacks. They could handle 4 or 5 cars on the 4% grades. Initially the switchbacks could only handle 7 or 8 cars, so the full potential of pusher engines could not be realized, but the switchbacks were soon lengthened to hold 10 to 12 cars.

An eastbound 25-car freight train would arrive in Wellington from Skykomish with a 2-8-0 Consolidation pulling and a 4-8-0 pushing. Traversing the 21 miles of 2.2% grades from Skykomish to Wellington at 5 to 6 miles per hour took 5 to 15 hours with water stops, meeting other trains, clearing rock slides, and other delays. At Wellington, the train would be broken into smaller trains of 10 to 12 cars for the trip over the switchbacks, with one or two locomotives on the front and another on the back. Seven-car passenger trains required three 4-6-0 locomotives, two on the front and one on the back, to cross the switchbacks. With luck, a train could get over the eight switchbacks to Cascade Station in an hour and a half, but in the winter the trip could take 36 hours. The normal rate of snowfall in Stevens Pass was 8 inches an hour, with 12 inches an hour common, and the snow often drifted 75 feet deep. The Great Northern employed hundreds of men to keep the switchbacks open and shovel out trains.

In 1898, the Brooks Works delivered to the Great Northern new 4-6-0s with 34,000 pounds of tractive effort, 130,000 pounds on the drivers, and 210 pounds of boiler pressures for passenger service and new 4-8-0s with 35,200 pounds of tractive effort, 172,000 pounds on the drivers and 210 pounds of boiler pressure for freight service. They were among the heaviest locomotives of their type at the time, and one of each were exhibited at the Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1898. The 4-8-0s introduced piston valves to the Great Northern and could haul 10 cars over the switchbacks without a pusher. This greatly sped up Stevens Pass operations and the Great Northern ordered more of them in 1900.

Construction of the 2.63-mile Cascade Tunnel began August 10, 1897, though work on the approaches had started in January. The tunnel with built as quickly as possible, using three shift of workers so construction could proceed 24 hours a day. The tunnel opened in December 1900, eliminating the switchbacks and eliminating the need to add and remove locomotives at Wellington and Cascade Station. It also reduced the maximum grade over Stevens Pass to 2.2% (the tunnel itself has a grade of 1.7% from east to west), reduced the time it took for trains to cross the pass by two hours, and ended the need to remove accumulations of up to 140 feet of snow at the summit every winter. Today, much of the switchbacks are forest service roads, including the road leading from Highway 2 to the Wellington Trailhead.

While the tunnel solved one problem, it ended up creating another. While the tunnel was oriented so that the prevailing west winds of the pass would clear it of smoke from steam locomotives in as little as 20 minutes, if wind was light or coming from another direction, the smoke and heat could be fatal to engine crews and passengers. The railroad tried to combat the problem, but as locomotives became larger and more powerful, the problems got worse. Some locomotives were equipped with extended smokestacks, but this was only partially effective. 200-degree temperatures were recorded in engine cabs, and eventually locomotives were equipped with gas masks.

In 1903, a passenger train with more than 100 passengers stalled in the tunnel when the coupling between the helper engine and the road engine failed. The crews tried to recouple the engines three times without success, and finally the helper engine ran ahead for help. By this time the conditions in the tunnel were seriously affecting the passengers and crew. The conductor reached the engine cab and found the engineer and fireman unconscious, and he collapsed himself before he could do anything. With the entire crew and most of the passengers unconscious, an off-duty railroad fireman traveling on the train as a passenger reached the engine cab and released the air brakes, allowing the train to roll out of the tunnel. Had he then lost consciousness, the train would have continued uncontrolled down the 2.2% mountain grade and eventually derailed, but the fireman managed to remain conscious long enough to make an emergency brake application once the train was in the open at Wellington. He received a citation for his heroic action and a personal check from James J. Hill for $1,000.

Meanwhile, the Great Northern was acquiring larger, more powerful locomotives. Between 1900 and 1906, the GN purchased large numbers of Class F 2-8-0 Consolidations from Rogers, Schenectady, Brooks and Cooke with 41,500 pounds of tractive effort, 175,000 pounds on the drivers and 210 pounds of boiler pressure. Two of the new 2-8-0s, one pulling and one pushing, could handle 1,050 tons at 5 to 6 miles per hour from Skykomish to Cascade Station, increasing freight train length from 25 to 35 or 40 cars. Rogers delivered new 4-6-2 locomotives for passenger service in 1905 and Baldwin delivered more in 1907 and 1909. In 1906, Baldwin delivered five Class L 2-6-6-2 Mallet articulated locomotives for pusher service on Stevens Pass, with 70,000 pounds of tractive effort, 316,000 pounds on the drivers, and 200 pounds of boiler pressure; they also introduced Walschaerts valve gear to the Great Northern. With a 2-8-0 pulling and a new 2-6-6-2 pushing, train tonnage was raised to 1,300 tons. 17 more Mallets were delivered in 1908, and with two Mallets, one pulling and one pushing, train tonnage increased to 1,600 tons.

Between the traffic density and the more powerful locomotives, the Cascade Tunnel was now full of smoke almost all the time, with conditions so hazardous that crews were essentially "flying blind" most of the time. In 1909, the railroad decided to put overhead wires in the tunnel to allow electric locomotives to pull trains through the tunnel.

The electrification system was unusual in that it would be the only three-phase railroad electrification in the Western Hemisphere. The system was chosen because at the time it was the only one that would permit regenerative braking on descending grades, which the railroad planned to use to control speeds on westbound trains in the tunnel. The three-phase system required two trolley wires plus the running rail to serve as the three conductors. Each of the four General Electric locomotives, Nos. 5000-5003, had two streetcar-like trolley poles at each end. Each locomotive had four 500-volt 275-horsepower induction traction motors with double extension shafts and a pinion on each end that meshed with an axle gear; there were two gears on each drive axle. The two two-axle trucks of each locomotive were hinged together with an articulated joint. The locomotives had to run at the speed that corresponded to the 375 rpm speed of the synchronous speed motors, which was 15 miles per hour. At that speed, three electric locomotives could pull a steam locomotive and a 1,600-ton train up the 1.7% grade from Wellington to Cascade Station. A 5,000-kilowatt power plant was built near Leavenworth, and a 33,000-volt transmission line brought power to the substation at the tunnel where it as stepped down to 6,600-volts for the trolley wires. Transformers on the locomotives stepped the power down to 500 volts for the traction motors. The electrification was placed in service on July 10, 1909. On August 11, 1909, both water wheels at the Leavenworth power plant failed and the electrics did not resume operation until September 9.

Historical Photos:

Cascade Tunnel, West Portal, 1910 (UW)

View out end of Cascade Tunnel at Wellington, 1910 (UW)

Electric Locomotives exiting Cascade Tunnel, 1913 (UW)

In 1910, the Great Northern began sending some of its old Cooke, Rogers and Schenectady 2-8-0s to the Baldwin Locomotive Works for rebuilding as M1 2-6-8-0 road Mallets. Baldwin lengthened the boiler and added a new six-coupled engine, moving the two-wheel lead truck forward. The six-coupled engines had low-pressure cylinders with a 35-inch bore and 32-inch stroke. The original 21-inch cylinders from the 2-8-0 were bored out to 23 inches and used as high-pressure cylinders. The resulting Mallet produced 78,000 pounds of tractive effort, had 350,000 pounds on its drivers, and was equipped with a feedwater heater and superheater. In 1911, Great Northern purchased the first of more than 200 3000-series Class O 2-8-2 Mikados with 61,500 pounds of tractive effort. A Mikado could bring a 60 car freight train weighing about 2,500 tons from Seattle to Skykomish, where two of the 2-6-8-0 Mallets would be added as helpers, one placed one-third of the way back and the other two-thirds of the way back. Together the three locomotives could bring the train to Tye in four and a half hours, with only a single 20 minute water stop at Scenic. At the Cascade Tunnel, these trains had to be broken in two, as three electric locomotives were not powerful enough to bring the entire train through the tunnel, and adding a fourth electric locomotive would have overloaded the power plant.

In 1923, the Division Point was moved from Leavenworth 22 miles east to Wenatchee. The time it took to split trains at Tye and reassemble them at Cascade Station had to be eliminated. In order to run four electric locomotives at the same time, the electrical engineers developed a “concatenated” traction motor connection (later known as the “Cascade” connection) that allowed the motors to run at half speed; at half speed four electric locomotives would not overload the power plant. The stop at Tye took only 15 minutes to cut out the 2-6-8-0 helpers. Freight trains, including the Mikado, could be hauled through the tunnel by four electrics, two in the front and two in the middle, in 22 minutes at 7.5 miles per hour. After cutting out the electrics at Cascade Station, the train could reach Wenatchee four hours later, 15 hours after departing Seattle. Passenger trains were pulled through the tunnel by two electrics at 15 miles per hour as before. The result was a surplus of electric motive power that led the Great Northern to consider extending the electrification to Skykomish.

Advancements in electrification technology led Great Northern to replace the original three-phase electrification with an entirely new 11,000-volt single-phase 25-Hertz system using new motor-generator electric locomotives. This system had been pioneered in 1925 by Henry Ford on the Detroit, Toledo & Ironton Railroad, but this would be the world’s first large-scale installation of this technology. Even though the new 8-mile Cascade Tunnel was starting construction and would soon eliminate the line from Scenic to Berne, Great Northern began installing the new system from Skykomish all the way to Cascade Station in December 1925, and the first of the new locomotives were delivered in 1926. During the installation in the Cascade Tunnel, a single-phase trolley wire was installed between the two three-phase wires, and with temporary short horns on the pantographs of the new electric locomotives, both types could use the tunnel until the changeover was complete. Puget Sound Power & Light provided the power for the new electrification, leasing the Great Northern’s original plant in the Tumwater Canyon which was converted to the new system, and building new plants at Skykomish and Wenatchee. The new electrification was placed in operation between Scenic and Cascade Station on February 27, 1927, and was extended to Skykomish on March 5, 1927.

The new electric locomotives could haul 3,500-ton freight trains from Skykomish to Tye in under two hours. Doubleheaded Mikados brought the train from Seattle to Skykomish, where one Mikado was cut off and an electric was added to each end. Eastbound passenger trains received one electric helper. Westbound trains continued to be steam powered until late 1928, and the electrics returned to Skykomish running light.

Meanwhile, the Great Northern was making additional improvements to the line on the east slope, replacing the original line through Leavenworth and the Tumwater Canyon with a new line called the Chumstick Line at a cost of $5,000,000. Surveys had begun in 1921 and A. Guthrie & Company began construction in July 1927. The new line diverged from the old line west of Wenatchee at Peshastin, proceeded up the Chumstick Valley, passed through the 2,601-foot Chumstick Tunnel into the Wenatchee Valley, crossed the Wenatchee River on a 360-foot steel bridge, passed through an 800-foot tunnel to Dead Horse Canyon, then passed through the 3,960-foot Winton Tunnel to rejoin the original line at Winton. Though this new line was only about a mile shorter than the old line, the maximum grade was reduced from 2.2% to 1.6%, the sharpest curves were 3 degrees instead of nine degrees, and 1,286 degrees of curvature and 1.5 miles of snowsheds were eliminated. The Great Northern decided to electrify this line as well, from Wenatchee to the east portal of the new Cascade Tunnel at Berne. The Chumstick Line and its electrification opened on October 7, 1928, and the Tumwater Canyon line was abandoned, eventually becoming the route of U. S. Highway 2. Leavenworth was bypassed by the main line and was served by a spur off the Chumstick Line.

From the opening of the Chumstick Line to the opening of the new Cascade Tunnel, a period of about three months, there was a gap in the electrification from Berne to Cascade Station, a distance of about 4.5 miles. The Great Northern never electrified this section of the line, which would be abandoned when the new tunnel opened. During those three months, the Great Northern was breaking in new electric locomotives by using them to pull passenger trains from Wenatchee to Berne. At Berne, a Mallet coupled onto the electric and pulled it and its train to Cascade Station, where the electric could again run on its own to Skykomish.

West Portal of the old Cascade Tunnel in 2000.

This Cascade Tunnel was abandoned in 1929 with the rest of this route when the new Cascade Tunnel opened between Scenic and Berne on January 12. The land was turned over to the U. S. Forest Service, which blocked the portals of the tunnel for many years. Eventually, the U. S. Government reopened the tunnel and used it as a storehouse for a time, but it had been largely ignored. It was once possible to walk through the tunnel, but a collapse & water buildup inside the tunnel has made it unsafe.

West portal of the old Cascade Tunnel in 2000.

The west portal of the first Cascade Tunnel is visible from Forest Service Road 050 leading to the Wellington Trailhead from the Old Cascade Highway (old Highway 2). This road is part of the old switchback route. Before the Iron Goat Trail was built, this was the closest easy access to this end of the tunnel.

West Portal of the old Cascade Tunnel in 1994.

This 1994 photo was taken from almost the exact same spot as the 2000 photo. In 1994, there was a beaten path down the slope to the portal, but it was very overgrown, and there was water flowing out of the portal.

Continue to Cascade Station…